How to assess watch movements beyond finishing

Read time: 4 min

There are many ways that a watch movement can be considered great. It could be its complication, simplicity, finishing, three-dimensionality, symmetry, asymmetry, materials, or any combination of all of these things. In today’s world, these various factors are not all created equal though. One from this list occupies a disproportionately large amount of attention in the watch world: finishing.

To be clear, there is nothing wrong with widespread attention to finishing. Our sense is that it has probably pushed the industry as a whole to create more well-finished timepieces. Brands know that their customers are taking deeper looks at their craftsmanship – that’s a good thing. Sometimes though, it can feel like a movement is entirely assessed by its finishing, leaving judgments of watchmaking one-dimensional.

That’s why we’re sharing some of the questions that we ask ourselves when examining movements. By no means is this one-size-fits-all. Every collector’s taste and focus will vary. Here, the intention is to add nuance to online discussions around what’s a great watch movement at the highest levels of independent watchmaking.

Does it look great at a distance?

A long time ago, Kees Engelbarts, the master engraver and watchmaker, told us something insightful on how to evaluate timepieces – “a watch is meant to be appreciated at arm’s length.” It’s an obvious, sometimes forgotten truth. The value of many interior angles, mirror polishing, circular graining on wheels, sandblasted mainplates, polished sinks, or ornate engraving doesn’t rest in proximity. Rather, it’s that all these shiny surfaces and varying textures allow light to dance when observing a movement from an appropriate distance.

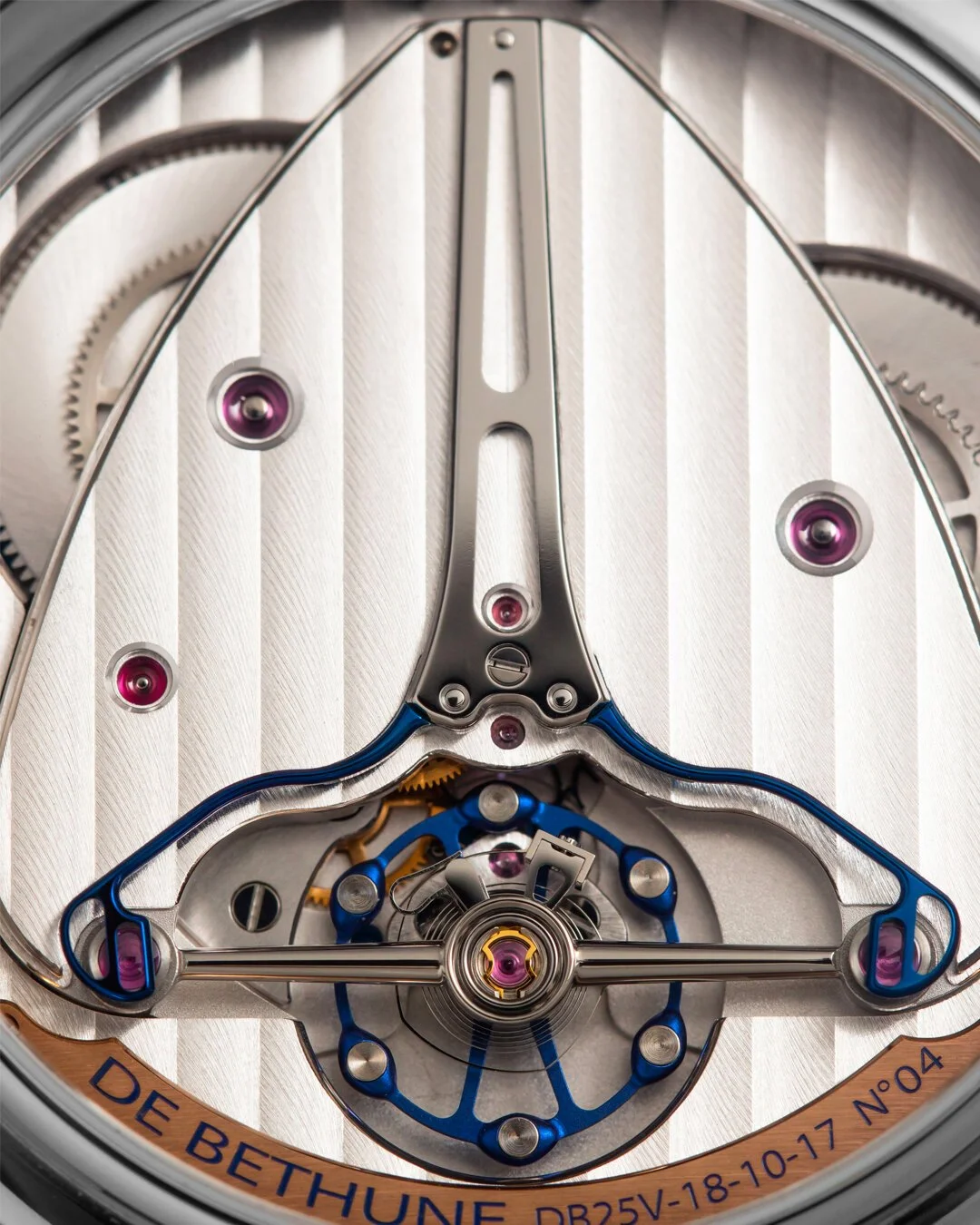

When zoomed in very tightly on a single bevel or screw sink, it’s easy to lose the idea that finishing across the entire movement should come together to create a stunning visual as a whole. Like an orchestra, it only sounds great when every instrument plays in unison. That’s what we examine when flipping a timepiece over, how does all the movement’s finishing play together in the light? There are stunning examples in independent watchmaking of brands that bring together finishing of all sorts in truly exceptional ways – Greubel Forsey, Kari Voutilainen, De Bethune. Each executes finishing of the highest quality on the most granular level, but it’s how all of the finishing comes together at arm’s distance that makes these three brands’ timepieces stand out.

Is there aesthetic cohesion through the whole watch?

Beyond all of the individual specifics of a movement, there’s always the question of aesthetic cohesion through the whole watch. Are there design elements that carry over to the movement from the dial? Is the dial extremely modern while the movement more classical? On a high level, does the movement fit the mood of the timepiece? Urwerk and MB&F do exceptionally well at creating timepieces that carry their aesthetics throughout.

Urwerk’s UR-100 and MB&F LM101 are both great examples of a movement that creates aesthetic cohesion across the entire timepiece. For the UR-100, there’s simply no world where a “classical” movement would align with the case and wandering satellite indication of time. The automatic rotor, labeled the "The Planetary Turbine Automatic System,” matches Urwerk’s aesthetic with the introduction of a seven-tooth wheel that engages a smaller tooth track to ensure the rotor doesn’t spin too quickly when in more active use. It’s a space-age movement for a space-age watch.

With the LM101, Max Büsser created a timepiece both classical and modern by balancing the aesthetics of both very carefully. Especially on the most recent LM101 Steel Blue, the juxtaposition between the shape of classical bridges and extremely modern NAC-coated black treatments creates the aesthetic cohesion required to make this movement elite.

Does the finishing fit the price tier?

Our last question has to do with aligning expectations with reality. We’ve written about how haute finishing should exist as its own category – something to differentiate brands like Greubel Forsey and Philippe Dufour from the watchmakers less interested in reaching that level of finishing perfection. Generally, we don’t expect every watchmaker to create timepieces with that degree of finishing. It’s also unreasonable to expect that degree of finishing for anything less than Greubel Forsey prices (>US$100,000). As it stands now, collectors can pick two out of the three – in-house movement, exquisite finishing, and price under $15,000. Though, the overall level of finishing in lower priced independent watches has improved significantly over the last 5 years.

Newcomers like Felipe Pikullik and Minhoon Yoo apply exceptionally high levels of finishing with many interior angles at prices under US$20,000. We’ve also long witnessed the high-level hand engraving work by Kudoke, such as on the Kudoke 2 day-night subdial, coming in at a price under US$10,000.

Finishing will always play a massive role in evaluations of movements in fine watchmaking, but there are so many other ways of appreciating a watchmaker’s work. Our hope is these three questions push collectors and enthusiasts to contemplate the quality of movements alongside their close looks at polishing.