How the “Indies” Shaped Modern Watchmaking As We Know It

When we started working on this article, the initial intention was to write about the origins and motivations behind the creation of AHCI, the Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants. As a bedrock institution in modern independent watchmaking, we expected to learn tons of new stories, locked in the memories of the association’s founders, independent watchmakers Vincent Calabrese and Svend Andersen. And we did.

What we didn’t expect to learn though; the origins of AHCI are directly connected to how modern luxury watchmaking came to be defined by high complications in the fallout of the Quartz Crisis. The story of the evolution, or revolution, in fine watchmaking revolves round independent watchmakers. After all, it is far from coincidence that AHCI was founded at the exact same time the watch industry was rising like a phoenix out of its own ashes.

For historical context, it’s important to recall that Swiss watchmaking in the 1940’s, 50’s, 60’s, and 70’s was by no means highly complicated. Omega’s Speedmaster (chronograph), Rolex’s Submariner (water-resistance technology), and the Rolex GMT were a much better representation of fine watchmaking before the Quartz Crisis than Patek Philippe’s legendary ref. 1518 or ref. 2499 perpetual calendar chronographs. The industry-wide push for high complications (tourbillons, minute repeaters, perpetual calendars, etc.) and in-house manufacturing only kicked off in the fallout of the Quartz Crisis in the 1980’s. This is a distinctly modern phenomenon. So what did independent watchmakers like Vincent Calabrese, Svend Andersen and their early AHCI collaborators have to do with this evolution? It all began in 1980.

Svend Andersen at work. Image Credits: Watches by SJX

1980 - The seeds of the future are sowed

As Calabrese narrated to us, watch brands leaned into different and innovative watches at the height of commercial crisis. As is common across all industries, developing technical and design innovations became the dominant business strategy against Quartz disrupting the Swiss watchmaking industry. More innovative, more elaborate or bold designs were surefire ways to move brands up in value and into markets with less competition and less price disruption. So when Calabrese’s horological invention, the Golden Bridge, was purchased by Corum for commercial use in 1980, this was effectively the foundation for a new approach to watchmaking. Relying heavily on outside watchmaking talents, few in numbers then, fine craftsmanship was revitalized throughout the next decade.

Vincent Calabrese (Left) and Golden Bridge Classic (Right)

Image Credits: Tidloscraft & Corum

Of course, none of this was clear while it was happening in real-time in 1980. At that point, the turn to high complications was an immediate issue of survival. In turbulent market conditions, damned be planning on decade-long timeframes. It must be said here, as Andersen and Calabrese testified, that technical complications and design innovations existed on the margins of the watch community then. Namely, knowledgeable Italian collectors, effectively acting as researchers and archivists of complicated timepieces in the history of horology, would regularly approach Andersen and Calabrese requesting unique pieces. These two watchmakers, as well as their peers at the time, had already built a wealth of experience through the 1970’s, creating historically-inspired, complicated timepieces. At that time, this simply wasn’t the common approach to watchmaking utilized by larger scale brands at the time.

Svend Andersen (Left) & Andersen Géneve Grande Jour et Nuit (Right)

Image Credits: Andersen Géneve

So with the seeds of complicated watchmaking sowed in 1980 with the Golden Bridge, Vincent Calabrese and Svend Andersen realized that there was a tidal wave of work coming, especially for their type of creativity and craftsmanship. Here is where AHCI enters the picture.

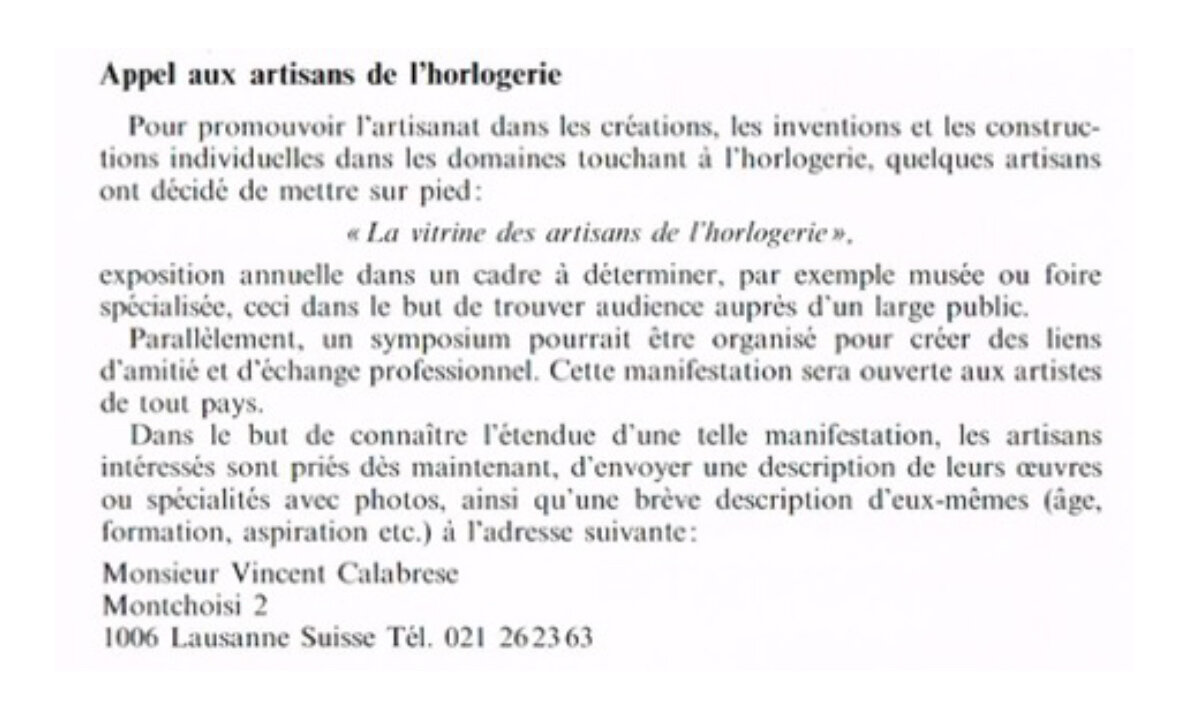

1984 - Banding together to ride the wave

We’re lucky that both Calabrese and Andersen are spectacular documentarians of their own history. Calabrese shared with us the original call for independent watchmakers for AHCI. At the time of its publication, AHCI was still an abstract idea with the hope of becoming more fleshed out through a meeting at Calabrese’s then home in Lausanne. One of the earlier appeals to bring independent watchmakers together, published in Chronométrophilia’s twice-annual bulletin in 1984, below is Calabrese’s call for what would be established as AHCI one year later in 1985. It reads as follows:

“Call for watchmaking craftsmen

To promote craftsmanship in creations, inventions and individual constructions in fields related to watchmaking, some craftsmen have decided to set up:

"The showcase of watchmaking craftsmen",

annual exhibition in a setting to be determined, for example a museum or a specialized fair, with the aim of finding an audience in a public environment.

At the same time, a symposium could be organized to create bonds of friendship and professional exchange. This event will be open to artists from all countries.

In order to know the extent of such an event, interested artisans are requested now to send a description of their works or specialties with photos, as well as a brief description of themselves (age, training, aspiration etc.) at the following address:

Mr. Vincent Calabrese”

When asked what the impetus was for such an association, Calabrese and Andersen said that they both feared being taken advantage of. As Calabrese said on our call, the idea behind what became AHCI was quite simple, “[w]e needed to stick together otherwise we’re going to be eaten whole by rising demand for our skills.” And as Calabrese pointed out, this susceptibility to being consumed whole by market demand had much to do with the state of the labor market at the time. Then, there weren’t nearly as many independent watchmakers as there are today, and most primarily, the nature of watchmaking education didn’t support the skills that brands demanded. For example, movement construction as taught now by watchmaking brands and schools didn’t exist in the educational curricula of yesteryear. Those that thought about and worked on new movement designs, like Calabrese’s Golden Bridge, were few and far between.

1985 - The beginning of AHCI, the beginning of the “complications arms race”

Two years later by 1985, Calabrese and Andersen were right, there was a tidal wave of demand for complications. The same year AHCI launched, so did the IWC Da Vinci Chronograph Perpetual, designed by Ludwig Oechslin (now the independent watchmaker behind Ochs & Junior). The next year, 1986, Audemars Piguet produced the first serially manufactured tourbillon. 1989, Patek Philippe produced the most complicated pocket watch for the brand’s 150th anniversary. The 1990’s would be defined by a “complications arms race” between the brands, culminating in IWC’s Il Destriero Scafusia (the Destroyer from Schafhausen) and Blancpain’s 1755. This was a kind of Ford vs. Ferrari competition across many brands, rife with public spats (staged or otherwise) by industry leaders like Jean-Claude Biver and Guenther Blumlein.

The iconic Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar Ref. 3750 - 1985 (Image Credits: IWC Schaffhausen)

Ultimately, AHCI watchmakers and other fast rising creative talents were the engineers of the arms race, working closely with brands to produce many of the timepieces listed above. Unfortunately, many of the contributions from independent watchmakers during this period are safeguarded by non-disclosure agreements. Some of the stories are more public though, George Daniels’ co-axial escapement is now the backbone of modern Omega, Calabrese’s Golden Bridge is still used by Corum, 40 years later. Through this formative period for modern watchmaking, AHCI members were the motor of complications development.

George Daniels. Image Credits: The George Daniels Education Trust.

The timing of AHCI and the rise of complications is far from coincidence. And its implications on our understanding of modern watchmaking are big.

From our vantage point, the importance of this story has a lot to do with the relationship between independent watchmaking and mainstream watchmaking. Often, we separate one from the other, placing each in neat boxes. The historical reality is significantly more complicated than these easy distinctions. As the origins of AHCI show, both independent watchmaking and mainstream brands were existentially tied to one another from the 1980’s onward. There would be very few foundational timepieces from big brands in the fallout of the Quartz Crisis without independent watchmakers, and inversely, many independent watchmakers are likely to still be buried in obscurity, fulfilling one-off timepieces for collectors (probably still Italian) without the industry-wide turn to high complications in fine watchmaking.

Of course, mainstream watchmaking doesn’t shed much light on this history, as it benefits independents significantly more than any of the big brands. Many of the biggest names in independent watchmakers today built their reputations initially by creating innovative horological solutions inside of big brands from Richard Habring at IWC, David Candaux and Eric Coudray at Jaeger-Lecoultre, or Andreas Strehler and John McGonigle at Audemars Piguet. There’s even a whole new generation of independent watchmakers who launched with reputations built at other, more established independent watchmakers - like a lineage. Rexhep Rexhepi and Ludovic Ballouard both coming out of F.P. Journe, Felix Baumgartner of Urwerk out of the workshop of Svend Andersen, the cycle now is set to continue and continue.

Felix Baumgartner of Urwerk. Credit: Urwerk

It also reshapes how we think of watchmaking as a craft, both today and historically. We know that there is a lot of lament over fine watchmaking skills dying at the hand of industrialized automation techniques. Time AEon Foundation notably works to preserve little-known, handmade watchmaking techniques, otherwise lost to history. If we take Calabrese and Andersen’s assessment of watchmaking in the 1970’s and 80’s seriously though, it appears that this was similarly an issue then and real progress has been made to push the boundaries of fine watchmaking and creativity. At the least, watchmaking curricula today provide a better foundation, with movement construction and complications are more widely taught and studied, for watchmakers to launch as independents.

Talking to Calabrese and Andersen opens Pandora's box to focus on the history of independent watchmaking and its relation to the history of modern watchmaking generally. Thanks to both Vincent and Svend for the time! And we’re always in search of great stories. If there’s something that you want to know more about specifically, email us with your idea here.